The History

of R&B

The History

of R&B

The Roots of the Rhythm: The Origins of R&B

To understand contemporary R&B—from SZA to Usher, from The Weeknd to Mary J. Blige—you have to understand the soil from which it grew.

Rhythm & Blues is not merely a musical genre; it is one of the most significant cultural forces of the 20th century. It is the trunk of the American musical tree, from which rock and roll, soul, funk, disco, and hip-hop all branched off.

But where did it begin? It didn’t start on a specific date. It was a slow-burning evolution born out of necessity, migration, technological shifts, and the undeniable resilience of African American culture in the post-World War II era.

Here is the story of how the blues got its rhythm.

The Primordial Soup: The Three Pillars

Before the term "Rhythm & Blues" existed, Black American music was largely categorized into three distinct streams. R&B was the inevitable collision of these three worlds.

The Blues (The Foundation)

Originating in the Deep South, the blues provided the emotional core and structural spine of R&B. It contributed the 12-bar structure, the lyrical themes of hardship, longing, and resilience, and the "blue notes" that gave the music its distinct, bittersweet melody.

Gospel (The Spirit)

The Black church has always been the training ground for astounding vocal talent. Gospel music provided the passion, the call-and-response vocal arrangements, and the transcendent, emotive singing style that would define R&B vocalists for decades to come. When sacred vocal stylings met secular lyrics, the sparks flew.

Jazz and Swing (The Instrumentation)

In the 1930s and early 40s, Big Band Swing was the pop music of the day. It provided the sophisticated instrumentation, the complex rhythms, and the dance-floor energy.

The Catalyst: The Great Migration and the Post-War Shift

The birth of R&B is fundamentally tied to sociology. During the first half of the 20th century, millions of Black Americans moved from the rural, agricultural South to the industrial cities of the North and West (Chicago, Detroit, New York, Los Angeles) in search of better jobs and escape from Jim Crow laws. This was The Great Migration.

This shift changed the sound of the music.

- Electrification: The acoustic, country blues of the Mississippi Delta couldn't be heard over the noise of a crowded Chicago nightclub. Musicians plugged in. The electric guitar and amplified harmonica became essential tools, making the music louder, rawer, and more urgent.

- The Death of the Big Band: During and immediately after WWII, maintaining a 20-piece swing orchestra became economically impossible due to travel costs and taxes on dance halls. Bandleaders had to downsize.

The Missing Link: "Jump Blues"

When the big bands shrank, they formed smaller "combos"—usually a rhythm section (drums, bass, piano), an electric guitar, and one or two saxophones.

To compensate for fewer instruments, the music had to be harder, faster, and more energetic to keep people dancing. This new style was called Jump Blues.

Jump Blues is the crucial bridge between pre-war swing and post-war R&B. It featured shout-style vocals, humorous lyrics, and a heavy, driving beat.

The Godfather: Louis Jordan

If there is one architect of early R&B, it is Louis Jordan. With his band, The Tympany Five, Jordan revolutionized Black popular music in the 1940s. Songs like "Caldonia" and "Choo Choo Ch'Boogie" defined the template: infectious rhythm, witty lyrics, and a screaming saxophone solo that took the place of the lead violin or trumpet in older jazz styles. Jordan proved that Black music could crossover to white audiences without losing its cultural identity.

The Sound of Early R&B

By the late 1940s, this new sound was coalescing. What defined it musically?

- The Backbeat: This is the heartbeat of R&B (and later, Rock & Roll). Instead of the smooth, four-beat pulse of jazz, R&B emphasized beats two and four. Snare-kick-SNARE-kick. It was undeniable and made you move.

- The Saxophone as King: Before the electric guitar took over in the rock era, the saxophone was the primary lead instrument in early R&B. Players like Illinois Jacquet and Big Jay McNeely were known for "honking" and "screaming" on their horns, driving audiences into a frenzy.

- Boogie-Woogie Piano: The driving, repetitive basslines of boogie-woogie piano players provided the uptempo engine for many early R&B tracks.

1949: The Name Change

For years, the music industry categorized all music made by and for Black Americans under the derogatory umbrella term "Race Records."

By the late 1940s, this term was not only offensive but inaccurate. The music was evolving rapidly, and its audience was diversifying. In 1949, Jerry Wexler, a young journalist for Billboard magazine (who would later become a legendary producer at Atlantic Records), realized the chart needed a new name.

He coined the term "Rhythm & Blues."

It was a functional description: the "Rhythm" came from the jump blues and swing beats, and the "Blues" came from the lyrical content and song structure. It gave a dignified name to a musical revolution already in progress.

The Engine Room: Independent Labels and Radio DJs

Major record labels like Columbia and RCA initially ignored this burgeoning, raucous music, viewing it as lacking commercial viability.

This left the door open for entrepreneurs. Independent labels ("indies") sprung up in key cities to service this new market:

- Atlantic Records (New York): Founded by Ahmet Ertegun and Herb Abramson, they brought a polished, yet soulful sound to the genre with artists like Ruth Brown and Big Joe Turner.

- Chess Records (Chicago): The home of electrified, urban blues that bled directly into R&B, making legends of Muddy Waters and Chuck Berry.

- King Records (Cincinnati): A powerhouse label that mixed country and R&B influences, famously launching James Brown.

Furthermore, the music needed a delivery system. Before the internet, there were charismatic Black radio DJs. Figures like Al Benson in Chicago or Rufus Thomas in Memphis played these records over the airwaves, acting as the tastemakers and gatekeepers for the new sound.

The Legacy Begins

By the start of the 1950s, the stage was set. The ingredients were mixed, the name was coined, and the infrastructure was built. R&B was ready to dominate the American soundscape, soon to birth its noisy younger sibling, Rock and Roll, and eventually evolve into the Soul music of the 1960s.

The 1960s: Motown and the Soul Explosion

If the 1950s were about R&B finding its feet, the 1960s were about R&B finding its voice—and its suit and tie.

This decade split the genre into two distinct, powerful streams: the polished, pop-perfection of Detroit (Motown), and the raw, gritty soul of the South (Stax/Atlantic).

The Assembly Line: Berry Gordy and Motown

In Detroit, a former auto worker named Berry Gordy founded Motown Records with a vision modeled after the Ford assembly line. He didn't just want to make hits; he wanted to make stars.

Motown’s impact on R&B was calculating and revolutionary:

- The Sound: It was infectious. Driven by the in-house band The Funk Brothers, the "Motown Sound" featured tambourines on the backbeat, melodic basslines (courtesy of the legendary James Jamerson), and call-and-response vocals derived from gospel.

- The Polish: Unlike the raw blues singers of the 50s, Motown artists were groomed. They attended "charm school," wore tuxedos and evening gowns, and executed synchronized choreography.

- The Crossover: Gordy marketed Motown as "The Sound of Young America"—not just Black America. Artists like The Supremes, The Temptations, Smokey Robinson, and a young Stevie Wonder broke down racial barriers, becoming household names in White suburbia just as the Civil Rights movement was heating up.

The Counter-Punch: Southern Soul

While Motown was smoothing out the rough edges, labels like Stax Records in Memphis and FAME Studios in Muscle Shoals, Alabama, were leaning all the way in.

This was "Deep Soul." It wasn't about choreography; it was about sweat.

- Otis Redding and Wilson Pickett brought a ferocious, unpolished energy that connected directly back to the church.

- Aretha Franklin (the "Queen of Soul") took the baton in the late 60s, demanding "Respect" and proving that R&B could be a powerful vehicle for female empowerment and political statement.

Furthermore, the music needed a delivery system. Before the internet, there were charismatic Black radio DJs. Figures like Al Benson in Chicago or Rufus Thomas in Memphis played these records over the airwaves, acting as the tastemakers and gatekeepers for the new sound.

The Shift: Social Consciousness

By the late 1960s, the happy-go-lucky love songs began to fade. As the Vietnam War raged and MLK was assassinated, R&B matured.

Motown’s own Marvin Gaye shattered the "pop factory" mold with What's Going On (1971), a concept album that addressed war, poverty, and ecology. It proved that R&B was an art form capable of high-level social commentary, setting the stage for the album-oriented soul of the 70s.

The Golden Age: The 1990s R&B Revolution

If the 1940s were the birth of R&B, and the 60s/70s were its soulful adolescence, the 1990s were its undisputed prime.

For many fans of the genre, this decade represents the pinnacle of artistry, commercial dominance, and cultural impact. It was an era where technical singing prowess met street-level authenticity, and slick studio production collided with raw hip-hop breakbeats.

The 90s didn't just continue the R&B tradition; it remixed it. The genre became the dominant sound of American youth culture, bridging the gap between the polished pop of Whitney Houston and the gritty reality of Wu-Tang Clan.

Here is how R&B seized the throne in the 1990s.

The Precursor: The New Jack Swing Hangovers

To understand the 90s boom, we have to look at how the 80s ended. The late 80s were defined by New Jack Swing, the genre pioneered by Teddy Riley (of Guy and Blackstreet). It was the first serious attempt to merge R&B melodies with hip-hop swing beats.

As the calendar turned to 1990, New Jack Swing was still the dominant sound. Janet Jackson’s Rhythm Nation 1814 (released late '89, dominated early '90s) and early tracks by Bobby Brown and Bell Biv DeVoe set the initial tempo. It was uptempo, dance-heavy, and highly produced.

But as hip-hop grew harder and more aggressive with the rise of gangsta rap, the polished veneer of New Jack Swing began to feel too clean. R&B needed to get grittier to keep up.

The Defining Moment: The Birth of Hip-Hop Soul

The true 90s sound wasn't born until a young A&R executive at Uptown Records named Sean "Puffy" Combs (later Puff Daddy/Diddy) realized that R&B artists didn't need to just sound like rappers; they needed to inhabit the same musical universe.

The philosophy was simple but revolutionary: Take a hard, rugged hip-hop breakbeat—often sampled from 70s funk or soul records—and place smooth, emotive R&B vocals on top of it.

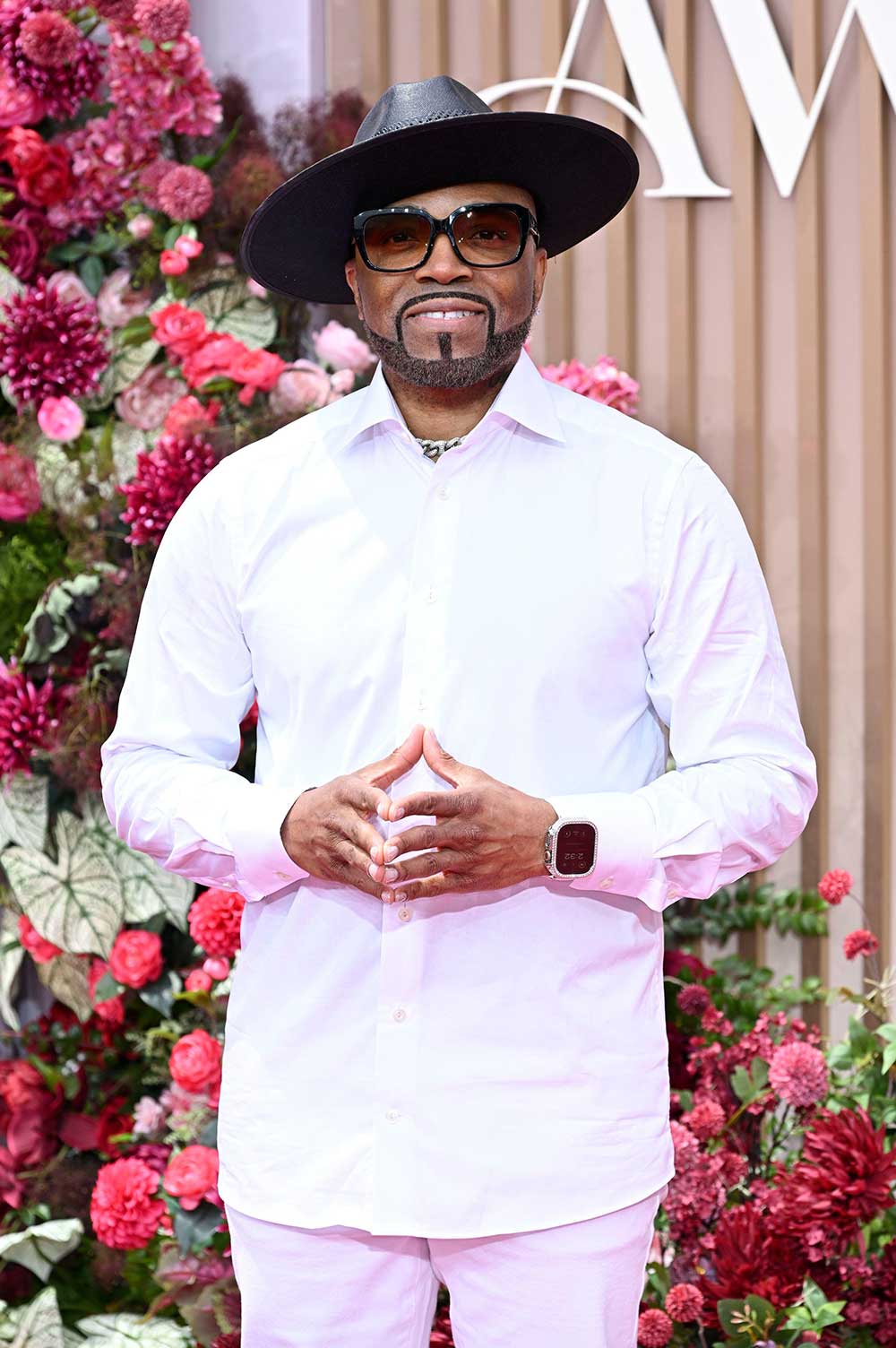

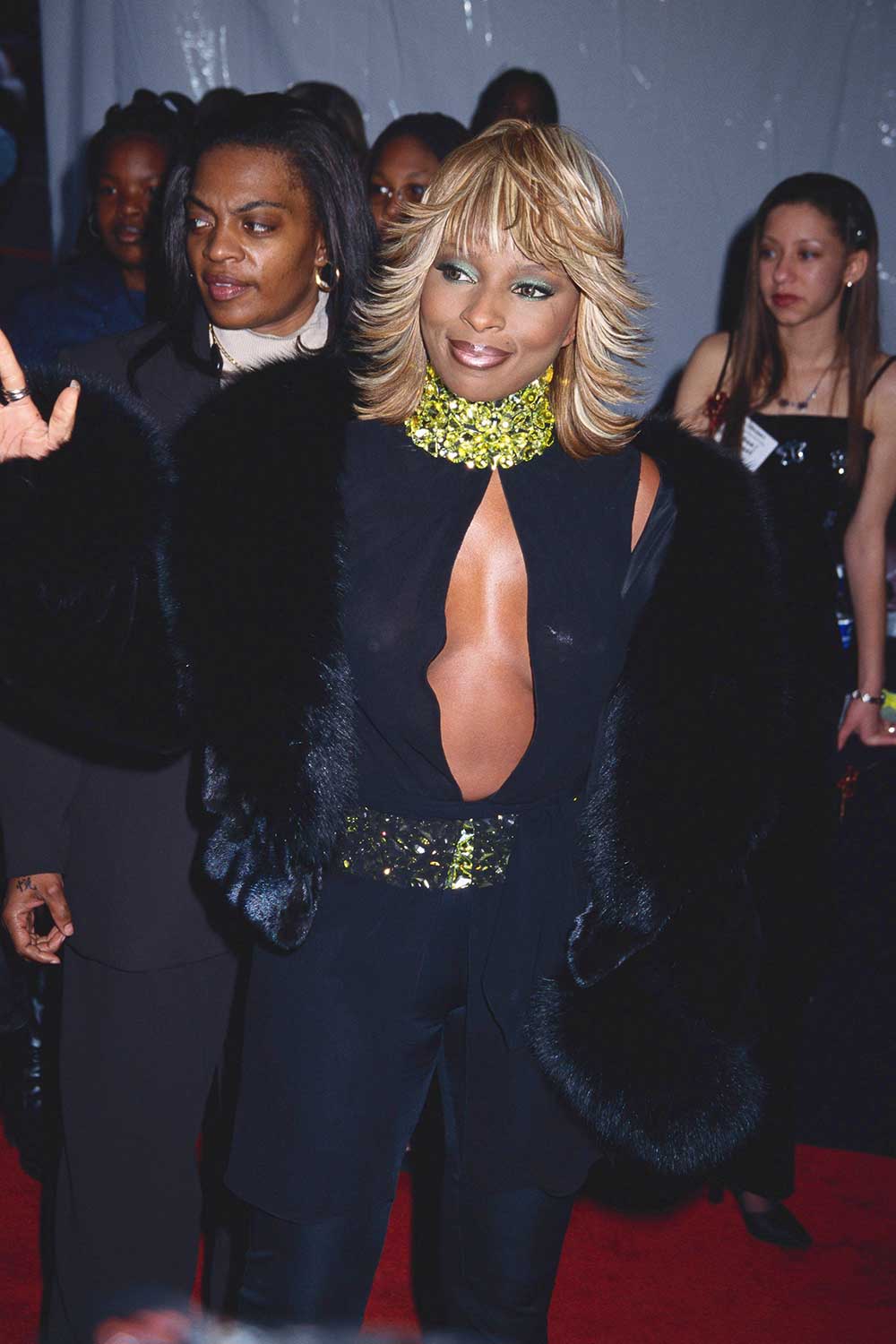

The Queen: Mary J. Blige

The archetype of this new sound was Mary J. Blige. Her 1992 debut, What's the 411?, produced largely by Puffy, changed everything. She wasn't a polished diva in a gown; she wore combat boots, baseball caps, and oversized jackets. She sang with a raw, painful vulnerability over beats that could have been on an EPMD record. She was christened the "Queen of Hip-Hop Soul," and her success proved that R&B could have street cred.

Suddenly, the "Remix" became essential. A hit R&B song wasn't complete until it had a remix featuring the hottest rapper of the moment. Mariah Carey's "Fantasy" remix featuring Ol' Dirty Bastard was a watershed moment where pure pop cemented its alliance with hardcore hip-hop.

The Sound Architects: The Super-Producers

The 90s was the era of the super-producer. These auteurs crafted distinct sonic landscapes that defined the decade.

- Babyface & L.A. Reid: While hip-hop soul was rising, Babyface kept the tradition of sophisticated, melodic, romantic R&B alive. He crafted massive hits for Boyz II Men, Whitney Houston, and Toni Braxton, focusing on lush arrangements and undeniable songwriting craft.

- Jimmy Jam & Terry Lewis: Continuing their reign from the 80s, they helped Janet Jackson evolve into a sexually liberated, socially conscious icon with janet. and The Velvet Rope.

- Sean "Puffy" Combs & The Hitmen: They dominated the mid-to-late 90s by mastering the art of the sample, turning 80s pop hits into 90s R&B gold for artists like Faith Evans, 112, and Total.

- Timbaland & Missy Elliott: In the late 90s, this duo introduced a futuristic, stuttering, syncopated sound. Their work with Aaliyah (One In A Million) and Ginuwine sounded like nothing else on earth, pushing R&B into avant-garde territory.

The Vocal Olympics & The Group Dynamic

Despite the focus on beats and production, the 90s remained an era fiercely dedicated to vocal excellence. It was a decade of melisma (vocal runs), power ballads, and intricate harmonies.

The Divas: Whitney Houston and Mariah Carey spent the decade trading the title of "world's greatest singer," delivering vocal performances of athletic prowess that remain the benchmark today.

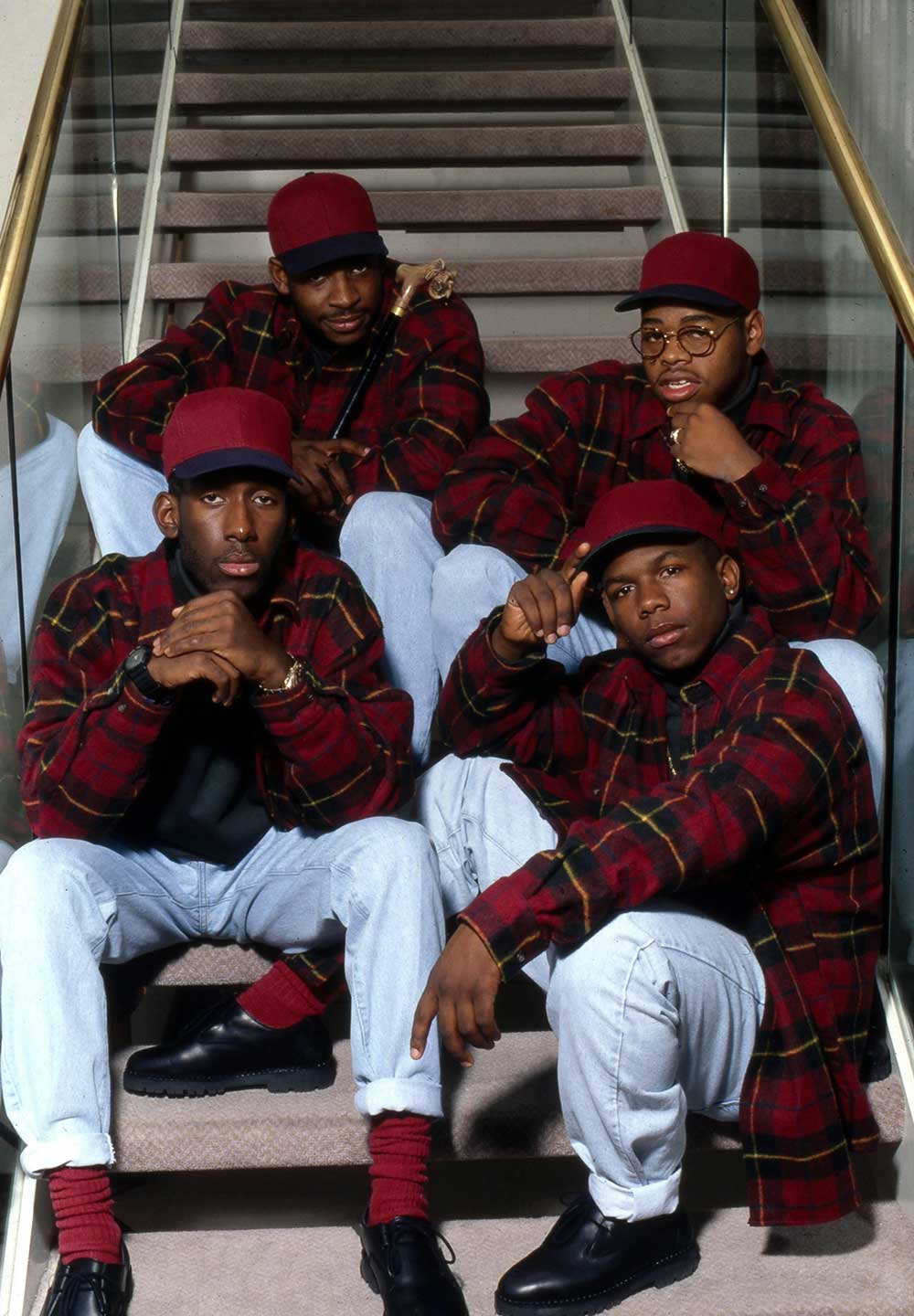

The Groups: The 90s was the final great era for R&B groups.

- Boyz II Men brought impeccable Motown-style harmonies back to the mainstream, becoming one of the biggest selling acts in history.

- Jodeci brought the "bad boy" aesthetic to R&B groups, blending gospel harmonies with hyper-sexualized lyrics and hip-hop swagger.

- TLC became the biggest girl group of all time by blending pop appeal, hip-hop attitude, and socially conscious lyrics (like "Waterfalls").

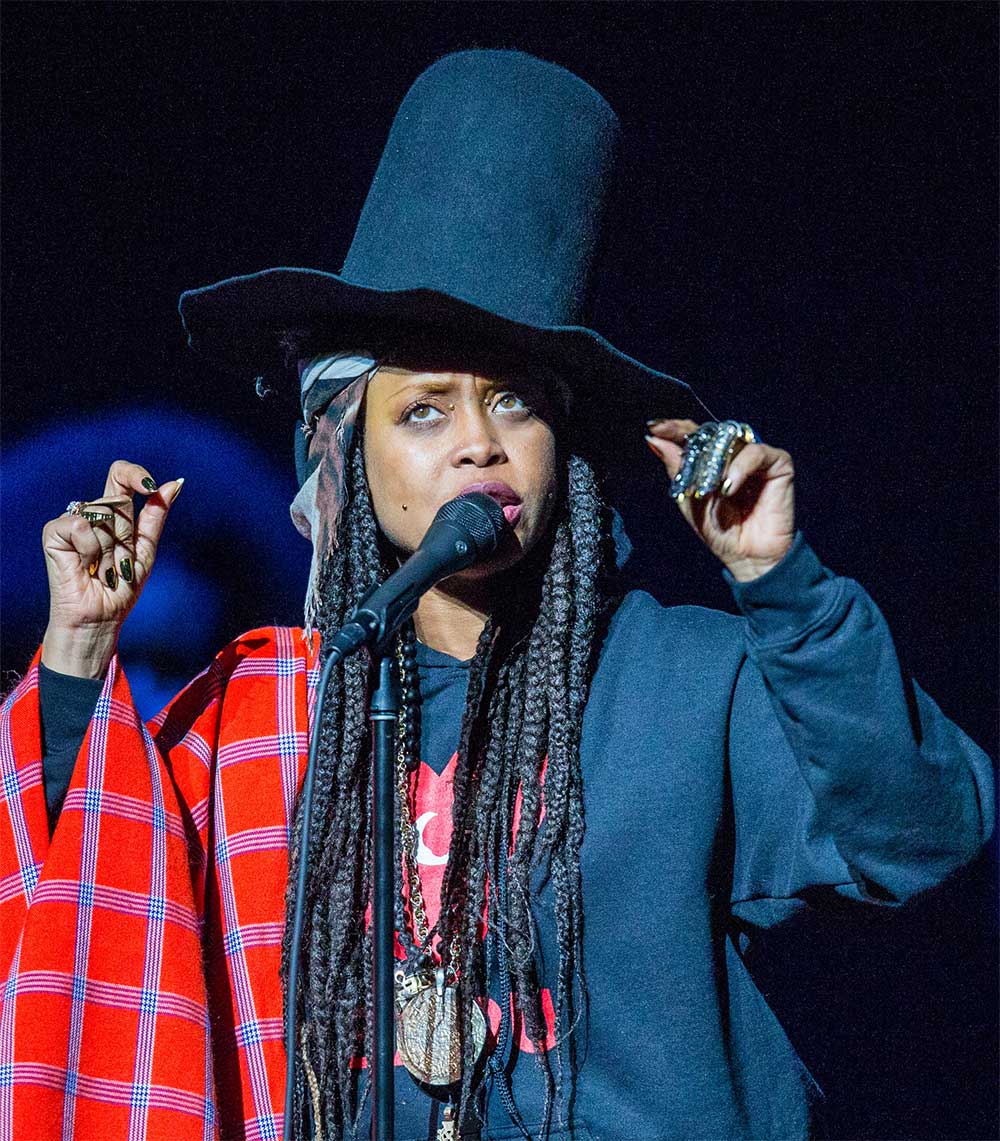

The Counter-Movement: Neo-Soul

By the mid-to-late 90s, some artists felt that commercial R&B had become too slick, too dependent on samples, and too focused on materialism (the "shiny suit era").

In reaction, a movement grew that looked backward to move forward. It eschewed digital production for live instrumentation, drawing inspiration from 70s jazz, funk, and the socially conscious soul of Marvin Gaye and Stevie Wonder.

Marketing executive Kedar Massenburg coined the term "Neo-Soul."

Artists like D'Angelo (Brown Sugar), Erykah Badu (Baduizm), and Maxwell (Urban Hang Suite) created music that was organic, earthy, bohemian, and deeply spiritual. It was the smoky basement alternative to the bright lights of the mainstream clubs.

The Legacy of the 90s

The 1990s ended with R&B as a global juggernaut. It had successfully absorbed hip-hop without losing its soul. The blueprint established in this decade—singing over trap beats, the rapper/singer collaboration, the blend of swagger and vulnerability—remains the fundamental architecture of mainstream music today.